Entraining Tones and Binaural Beats

Sound can have profound effects on people. Although sounds appear to be a personal experience, humans around the world are hard-wired to have similar experiences to certain sounds. Spooky sounds can make people feel anxious and scared, whereas up-tempo sounds can make people feel energetic and lively. The sound of chirping birds in a forest produces even harmonics and will be more relaxing than the sounds from a factory (odd harmonics), not just because of the associations people make with sounds of nature versus factories, but also because of the harmonic content. However, if a person has a fear of birds (ornithophobia), then chirping birds might be quite distressing.

Auditory Entrainment CDs and audio downloads for the purposes of auditory entrainment (AE) have become very popular. There are presently upwards of 100 producers of “entraining” audio for relaxation, cognition, sleep, performance, etc. Auditory entrainment is exempt from US-FDA, Health Canada and European Community Regulations as a medical device in its pure form unless medical claims are being made. While audio stimulation methods would likely have a dissociative aspect to them, do they produce entrainment?

Physiology of Auditory Entrainment: In order for entrainment to occur, a constant, repetitive stimulus of sufficient strength to “excite” the thalamus must be present. The thalamus then passes the stimuli onto the sensory-motor strip, the cortex in general and associated processing areas such as the visual and auditory cortices in the temporal lobes

Figure 1. Neural Pathways of the Auditory System

Figure 1 shows the neural pathway of hearing. Sounds pass through the ear into the cochlea where the auditory nerves are located. The signals from these nerves are carried down to several locations. One is called the superior olive. In the superior olive, the minute differences in the timing and loudness of the sound in each ear are compared, and from this you can determine the direction the sound came from. Another point is the medial geniculate (a relay point) from where auditory information is then transmitted into the thalamus on its way to the main cortex and the auditory cortex simultaneously. Entrainment only occurs from the thalamic relay point and not through the olivary bodies where binaural beats are heard. This also means that while listening to entraining media clicks, pops, scratches and other interfering sounds will produce their own evoked potentials within the brain and temporarily impede the entrainment process. “Cleanliness” of sound is an all-important, yet often overlooked aspect of AE. By definition, entrainment occurs when the brain wave frequency duplicates that of the stimuli, whether audio, visual or tactile (Siever, 2003) as can be seen on an EEG. When using tones for the purpose of entrainment, the result needs to meet both physiological (the actual evoked response) and psychological (a person’s emotional acceptance of the tones) criteria to be effective. Personal acceptance is an important factor when choosing the “right” kind of tone

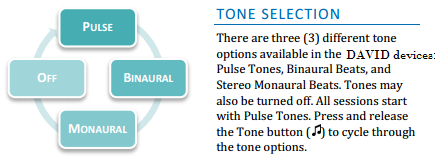

The three auditory sounds often used for entrainment are clicks, isochronic tones and binaural beats. Research has shown that “clicks” produce powerful AE (Chatrian, Petersen & Lazarte, 1959). It was observed that clicks produced as powerful an effect in the auditory region as light flashes do at the same frequency in the visual cortex. However, most people have a psychological dislike towards clicks and respond with apprehension or anxiousness, which will result in a poor AE experience. Therefore, Mind Alive Inc., only includes Isochronic Tones (Pulse Tones), Binaural Beats, and Monaural Beats on our devices.

Isochronic Tones: Isochronic tones are evenly spaced tones which turn on quickly and off quickly. They are an effective auditory entrainment method because they elicit a strong auditory evoked response via the thalamus and most people find them tolerable. They are exceptionally dissociating and have hypnotic qualities, particularly when slightly randomized in frequency. Audio and visual entrainment (AVE) at 18.5 Hz has also been shown to produce dramatic increases in EEG amplitude at the vertex (Frederick, Lubar, Rasey, Brim, & Blackburn, 1999).

When comparing flashing light with evenly spaced auditory tone pulses (isochronic tones), it was found that with: a) eyes-closed 18.5 Hz. photic entrainment increased 18.5 Hz EEG activity by 49%; b) eyes-open auditory entrainment produced increased 18.5 Hz. EEG activity by 27%; c)eyes-closed auditory entrainment produced increased 18.5 Hz EEG activity by 21%. It’s easy to see that auditory entrainment from isochronic tones produces about half of the entrainment effects as compared to flashing light.

Isochronic tone stimulation has shown promise as a singular therapeutic modality for treating tension and pain (Manns, Miralles, & Adrian, 1981). In this study, people suffering with myofascial pain and TMJ dysfunction were split into two groups — group A, those with symptoms for less than one year (n=14), and group B, those with symptoms for longer than one year (n=19). They received 15-minute sessions of auditory entrainment (AE) consisting of isochronic, pure (evenly-pulsed sine wave) tones, followed by 15 minutes of EMG feedback and concluding with 15 minutes of AE and EMG feedback combined, for an average of 14 sessions. The study clearly shows greater reductions in EMG activity during AE. Table 1 shows the reduction in MPD/TMJ symptoms following treatment.

Table 1 TMJ Symptoms Following Audio Entrainment and EMG Feedback

Symptom | Group A (n=14) | Group B (n= 19) | ||

Participants with symptoms (%) | Participants with symptoms (%) | |||

Pre Tx | Post Tx | Pre Tx | Post Tx | |

| Bruxism | 100 | 7 | 100 | 32 |

| Emotional tension | 100 | 14 | 100 | 21 |

| Muscle fatigue | 93 | 0 | 74 | 21 |

| Insomnia | 57 | 0 | 53 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 21 | 0 | 53 | 0 |

| Headache | 93 | 0 | 74 | 0 |

| TMJ Pain | 64 | 0 | 47 | 0 |

| Masticatory muscle pain | 71 | 0 | 58 | 9 |

| Neck muscle pain | 79 | 9 | 79 | 26 |

| Otalgia | 79 | 9 | 32 | 17 |

| Mastoid process pain | 43 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

| Articular clicking | 50 | 29 | 68 | 54 |

| Mandibular deviation | 79 | 36 | 84 | 56 |

| Restricted opening | 43 | 0 | 16 | 0 |

Binaural vs. Monaural Beats

Binaural beats were first discovered in 1839 by a German experimenter called H. Dove. Binaural beats were first thought to be a special case of monaural beats, but they have since been shown to be two distinct entities. Binaural beats are generated by presenting two different tones at slightly different pitches (or frequencies) separately into each ear. Binaural effects are produced within the brain by the neural output from the ears and created within the olivary body within the brain, in its attempt to “locate” the direction of the sound based on phase. EEG studies have shown that binaural beats do NOT produce any significant entraining effect. Binaural beats cannot generate entrainment because, as two steady tones, they do NOT impact the thalamus. Although binaural beats do not produce a significant entrainment effect, they do have some hypnotic and relaxing effects by way of dissociation (as does white noise and music). This may be, in part, due to the Ganzfeld effect. This is the process where the mind quietens as a result of having a monotonous sensory input. A natural example of the Ganzfeld effect may be experienced while sitting in a large field in the country while staring into the wide, blue sky while listening to the white noise from the fluttering of leaves on the trees – away from the noise and other stimulation of urban life. Because of the Ganzfeld effect, binaural beats, through passive means, may help a person to relax. And, because binaural beats are processed in the olivary body, they may have some clinical applications. Some people with neurological damage have trouble localizing the source of a sound such as the snapping of a finger. Because these people cannot hear binaural beats either, binaural beats could be used to determine where the neurological damage lies within the brain.

Studies on Binaural Beats

Study 1: Oster (1973) used an EEG oscilloscope to conclude that binaural beats produce very small evoked potentials within the auditory cortex of the brain which means that they are of little benefit in producing AE.

Study 2: Foster, another researcher of binaural beats, found that binaural beats in the alpha frequency produced no more alpha brainwaves than listening to a surf sound. His conclusion was: The analysis of variance of the data revealed that there were no significant differences in alpha production either within sessions across conditions or across sessions. Although alpha production was observed to increase in the binaural-beats condition early in some sessions, a tendency was observed for the subjects to move through alpha into desynchronized theta, indicating light sleep. Subjective reports of “dozing off” corroborated these observations. These periods of light sleep — almost devoid of alpha — affected the average alpha ratios.

Study 3: Wahbeh, et al., (2007) ran a small randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Objectives: When two auditory stimuli of different frequency are presented to each ear, binaural beats are perceived by the listener. The binaural beat frequency is equal to the difference between the frequencies applied to each ear. Our primary objective was to assess whether steady-state entrainment of electroencephalographic activity to the binaural beat occurs when exposed to a specific binaural beat frequency as has been hypothesized. Our secondary objective was to gather preliminary data on neuropsychologic and physiologic effects of binaural beat technology. Design: A randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled crossover experiment in 4 healthy adult subjects. Intervention: Subjects were randomized to experimental auditory stimulus of 30 minutes of binaural beat at 7 Hz (carrier frequencies: 133 Hz L; 140Hz R) with an overlay of pink noise resembling the sound of rain on one session and control stimuli of the same pink noise overlay, but without the binaural beat carrier frequencies used on the other session. Outcome Measures: Data were collected during two separate sessions 1 week apart. Neuropsychologic and blood pressure data were collected before and after the intervention; electroencephalographic data were collected before, during, and after listening to either binaural beats or control. Neuropsychologic measures included State Trait Anxiety Inventory, Profile of Mood States, Rey Auditory Verbal List Test, Stroop Test, and Controlled Oral Word Association Test. Spectral and coherence analysis was performed on the electroen-cephalogram (EEG), and all measures were analyzed for changes between sessions with and without binaural beat stimuli. Results: There were no significant differences between the experimental and control conditions in any of the EEG measures. There was an increase of the Profile of Mood States depression subscale in the experimental condition relative to the control condition (p = 0.02). There was also a significant decrease in immediate verbal memory recall (p = 0.03) in the experimental condition compared to control condition. Conclusions: We did not find support for steady-state entrainment of the scalp-recorded EEG while listening to 7-Hz binaural beats. Although our data indicated increased depression and poorer immediate recall after listening to binaural beats, larger studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Study 4: Stevens, et al., (2003) conducted a study where they looked for increased theta brainwave activity following theta binaural beats.Abstract: The present study offered a constructive replication of an earlier study which demonstrated significant increases in theta EEG activity following theta binaural beat (TBB) entrainment training and significant increases in hypnotic susceptibility. This study improved upon the earlier small-sample, multiple-baseline investigation by employing a larger sample, by utilizing a double-blind, repeated measures group experimental design, by investigating only low and moderate susceptible participants, and by providing 4 hours of binaural beat training. With these design improvements, results were not supportive of the specific efficacy of the theta binaural beat training employed in this study in either increasing frontal theta EEG activity or in increasing hypnotic susceptibility. Statistical power analyses indicated the theta binaural beat training to be a very low power phenomenon on theta EEG activity. Furthermore, we found no significant relationship between frontal theta power and hypnotizability, although the more hypnotizable participants showed significantly greater increases in hypnotizability than the less hypnotizables. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2006 APA, all rights reserved).

Study 5: Ulam (2006) studied the brainwave entraining effects of binaural beats: Abstract: The study investigated the use of binaural beat frequencies in inducing entrainment of synchronous brain wave activity within the theta frequency band. Subjects consisted of 43 volunteers recruited from psychophysiology courses offered at the California State University at Fresno. Each subject served as his own control, receiving binaural beat stimulation, monaural beat stimulation, and monaural tone stimulation. Subjects were randomly assigned to three groups in which the order of treatments was counterbalanced. Subjects were naive as to the hypotheses, and treatments were delivered under double-blind conditions. Binaural beat stimulation was produced by the Hemi-Sync Synthesizer, Model 201B. Both 440 Hz and 436 Hz tones were used for stimulation conditions containing beat frequencies, while a 440 Hz tone alone was used for the monaural tone condition. EEG activity was recorded from Fp2, C2, O2 and T5 and T6 scalp locations, using an extension of the 10-20 International System. EEG activity was acquired with BFC5000-4 with on-line Spectral Analysis unit. An integrated, coherent averaging circuit was used to measure phase synchrony across the five electrode locations. Spectral data were quantified into absolute and relative power of theta at each electrode site, including the coherent averaging circuit channel. A three-factor, mixed ANOVA revealed no significant differences between groups on treatments, indicating that binaural beat stimulation produced no greater inducement of theta than the control conditions and that theta was no more synchronous during binaural beat stimulation than during control conditions. Suggestions for future research emphasized the inclusion of controls for the attentional focus of subjects and use of coherent averaging for each channel of the EEG in a more traditionally evoked potential paradigm. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2006 APA, all rights reserved)

Study 6: Kennerly (2004) performed an EEG analysis and found increased theta brainwave activity during theta binaural beat stimulation. However, this study is flawed because it is well know that theta brainwave activity increases a few minutes after the eyes are closed. The study by Wahbeh and the other by Ulam, where they compare the EEG results against a control group is the only credible way to know for certain.Abstract: The current pilot study was conducted to determine the effect of binaural beat audio on brainwave activity. Digital EEG for QEEG analysis was obtained from 30 research volunteers during a baseline condition and during ten minutes of binaural beat audio. Binaural beat audio was produced with the software package Brainwave Generator. Significant changes from baseline were noted in QEEG during the presentation of binaural beat audio. Entrainment occurred, on average, five minutes after the presentation of the binaural beat audio. The changes seen in QEEG were congruent with the presence of a frequency following effect. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2006 APA, all rights reserved)

Study 7: Lane, et al., (1998), conducted a binaural beat study using beta beats and theta beats during a psychomotor task. Unfortunately no EEG data was collected, so it’s difficult to determine if the beats entrained brainwaves or if beta beats increased the participants’ ability merely through increased arousal like rock music does. Abstract: This study compared the effects of binaural auditory beats in the EEG beta and EEG theta/delta frequency ranges on mood and on performance of a vigilance task to investigate their effects on subjective and objective measures of arousal. 29 participants (aged 19-51 yrs) performed a 30-min visual vigilance task on 3 different days while listening to pink noise containing simple tones or binaural beats either in the beta range (16 and 24 Hz) or the theta/delta range (1.5 and 4 Hz). However, participants were kept blind to the presence of binaural beats to control expectation effects. Presentation of beta-frequency binaural beats yielded more correct target detections and fewer false alarms than presentation of theta/delta frequency binaural beats. In addition, the beta-frequency beats were associated with less negative mood. Results suggest that the presentation of binaural auditory beats can affect psychomotor performance and mood. This technology may have applications for the control of attention and arousal and the enhancement of human performance. (PsycINFO Database Record (c) 2006 APA, all rights reserved)

Study 8: Le Scouarnec, et al. (2001) found that binaural beat tapes in the theta range produced significant reductions in anxiety. It is not known if binaural beat tapes would have been better than white or pink noise, but the results are encouraging. Abstract: Recent studies and anecdotal reports suggest that binaural auditory beats can affect mood, performance on Objective: To determine whether mildly anxious people would report decreased anxiety after listening daily for 1 month to tapes imbedded with tones that create binaural beats, and whether they would show a definite tape preference among 3 tapes. DESIGN: A 1-group pre-post test pilot study.vigilance tasks, and anxiety. Setting: Patients’ homes.Participants: A volunteer sample of 15 mildly anxious patients seen in the Clinique Psyché, Montreal, Quebec. Intervention: Participants were asked to listen at least 5 times weekly for 4 weeks to 1 or more of 3 music tapes containing tones that produce binaural beats in the electroencephalogram delta/theta frequency range. Participants also were asked to record tape usage, tape preference, and anxiety ratings in a journal before and after listening to the tape or tapes. Main Outcome Measures: Anxiety ratings before and after tape listening, pre- and post-study State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scores, and tape preferences documented in daily journals. Results: Listening to the binaural beat tapes resulted in a significant reduction in the anxiety score reported daily in patients’ diaries. The number of times participants listened to the tapes in 4 weeks ranged from 10 to 17 (an average of 1.4 to 2.4 times per week) for approximately 30 minutes per session. End-of-study tape preferences indicated that slightly more participants preferred tape B, with its pronounced and extended patterns of binaural beats, over tapes A and C. Changes in pre- and post-test listening State-Trait Anxiety Inventory scores trended toward a reduction of anxiety, but these differences were not statistically significant. Conclusions: Listening to binaural beat tapes in the delta/theta electroencephalogram range may be beneficial in reducing mild anxiety. Future studies should account for music preference among participants and include age as a factor in outcomes, incentives to foster tape listening, and a physiologic measure of anxiety reduction. A controlled trial that includes binaural beat tapes as an adjunctive treatment to conventional therapy for mild anxiety may be warranted. Monaural beats, however, can produce brainwave entrainment because they are in beat form before they strike the ear drum, which impacts the thalamus, and therefore the cortex. Only monaural beats are the result of the arithmetic (vector) sum of the waveforms of the two tones as they add or subtract from one another, becoming louder and quieter and louder again.Monaural and binaural beats are rarely encountered in nature, but in man-made objects, monaural beats occur frequently. For example, two large engines running at slightly different speeds will send “surges” of vibrations through the deck of a ship or jet plane. The lower pitched tone, is called the carrier and the upper tone is called the offset. EEG studies of monaural beats have conclusively shown that monaural beats produce a frequency following response in the contralateral hemisphere of the brain, and are therefore quite useful for entrainment. Figure 4 shows how a 24 Hz monaural beat is produced by mixing two separate tones with a 24 Hz difference between them.

Figure 2. Vector Summation of Tones at Two Different Frequencies Produces Monaural Beats.

To hear monaural beats, both tones must be of the same amplitude. However binaural beats can be heard when the tones have different amplitudes. They can even be heard if one of the tones is below the hearing threshold. Noise reduces the perceived volume of monaural beats whereas noise actually increases the loudness of binaural beats (Oster, 1973). When a person hears fewer than three binaural beats a second, the beats appear to move back and forth across the head. A perception of movement is a result of the way the brain processes sounds. For low frequencies, the brain determines the beat of the sounds by detecting the difference in phase angle between the two sounds. The brain cannot process phase relationships well at higher frequencies and therefore detects the differences in amplitude of sounds striking the ear at the same time. This explains why one perceptive difference between monaural and binaural beats is that monaural beats can be heard at any pitch whereas binaural beats are best perceived at lower pitches and are best observed at about 440 Hz. (Binaural beats using carrier frequencies above 900 Hz are typically not noticeable.) When the two tones used to make a binaural beat are far enough apart in frequency, they are perceived as two separate tones because the changes in the phase relationship between the two tones occur too quickly for the brain to interpret them as being related. J. Licklider, of MIT, performed a test to measure the spectrum of binaural beats that people could perceive at various carrier frequencies. He found that the quickest beat that could be heard before the brain perceived it as two distinct tones was 25 Hz at a carrier frequency of about 440 Hz. In other words, if the two tones are more than 25 Hz apart, then two separate tones are heard, not a binaural beat. At carrier frequencies above and below 440 Hz, the perception of two separate tones occurs at a lower beat frequency. Figure 7 is a graph showing the highest perceivable beat frequency in relation to the carrier frequency.

Figure 3. Frequency Used and Hearing Perception.

Since the 1980s, binaural beats have been popularized under the trade names “Hemisync” or “Holosync” and other groups have invented their own terms. These groups have sold hundreds of thousands of tapes and CDs over the years. This has also prompted dozens of other uninformed groups to manufacture binaural beat CDs and MP3s for all kinds of applications (depression, insomnia, stress, anxiety, cognitive improvements, etc).

Binaural beats are not very noticeable because the difference between loud and quiet is only 3 dB That’s a ratio of 2:1 |

Isochronic tones and mono beats have a 50 decibel difference between loud and quiet That is a 100,000-to-1 ratio |

Dissociation Dissociation is a term often associated with pathology. However, there are many physiological benefits derived from the positive form of dissociation, such as those which occur when we meditate, exercise, go hiking, read a good book, watch a movie or enjoy a sporting event, because we get drawn into the present moment and dissociate from all of our daily worries, anxieties and the resulting unhealthy mental chatter. Regardless of the activity, this type of dissociation reduces our overall stress load and is healthy. In essence, when we focus on something, we dissociate from other things (Siever, 2000). The saying, “a change is as good as a rest,” has much more physiological truth to it than initially meets the eye.

Several techniques such as dot staring and stimulus depression have been shown to induce dissociation (Leonard, Telch, & Harrington, 1999). Audio-analgesia using white noise and/or music has been shown to effectively increase pain threshold and pain tolerance during a dental procedure (Gardner & Licklider, 1959; Gardner, Licklider, & Weisz, 1960; Schermer, 1960; Monsey, 1960; Sidney, 1962; Morosko & Simmons, 1966). Auditory stimulation can be very dissociating. Almost anyone can be completely drawn into a favorite song and lose all track of life and stress around him or her. For example, slaves and prisoners throughout history have used song as a means to dissociate from the stress of hardship and segregation. Dental patients often suffer anxiety before and during dental appointments (Lazarus, 1966, Dewitt, 1966, Corah & Pantera, 1968). Of all the dental procedures, root canal (endodontic) therapy is the most feared (Morse & Chow, 1993). A study using visual entrainment (VE) to reduce anxiety during a root canal procedure found that by adding relaxing (dissociating) music, the anxiety was further reduced (Morse 1993). This study involved three groups of 10 subjects. The groups consisted of one group receiving 10 Hz AVE; a second group receiving 10 Hz AVE plus an alpha relaxation tape (developed by Shealy) simultaneously, and a control group (Figure 1). The study confirmed that the part of a root canal procedure that produces the greatest anxiety is the Novocaine™ injection, pushing average heart rate up to 107 bpm. The group using VE had an average heart rate of 93 bpm, while the group that was further dissociated (VE and music), had an average heart rate of 84 bpm. Figure 4. Heart Rate during a Root Canal Procedure

What works best? Our own experience and observations have led us to believe that isochronic “pulse” tones consisting of a pure tone (sine wave) with a pitch of about 150 to 180 Hz have the best entrainment value as they meet the personal acceptance of most people. Some people prefer to mix white noise or other continuous sounds with entraining tones to help block out unsettling background noise. Teenage boys generally prefer a “buzzy” synthesizer sound such as are produced by guitar “distortion” pedals used in some rock bands. Figure 5 shows a typical oscilloscope tracing of isochronic tones produced from a DAVID device when the tones for both ears are synchronized and alternating (left/right) stimulation. Figure 5. Isochronic Tones in Synchronized (Focus) and Alternate (Expand) Stimulation.